BEFORE AND AFTER EXERCISE

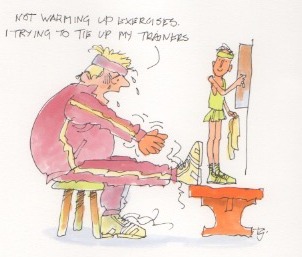

Warming up

For any exercise you are advised to warm up before starting – for anything from a few minutes to half an hour. This is received wisdom for exercise professionals and if you take part in an supervised exercise class the warm up is an integral part of the session. The purpose is to loosen up and warm the joints, muscles and tendons, making them more flexible and ready for exercise and thus less vulnerable to injury. It certainly sounds like something sensible to do. However avoid spending too much time on warming up – if you have limited time for exercising on your own, start slowly and use this as your warm up.

Stretching

Another commonly promoted preliminary to taking exercise is stretching. Again the idea is to prepare the muscles and tendons for the more violent changes about to be brought on by exercise. There are two forms of stretch – static and dynamic. They are both beloved by exercise professionals but they too have very little evidence to support. Indeed it has been shown that static calf muscle stretches actually increases the risk of injury among runners, perhaps by reducing the strength in the stretched muscles. There is some evidence that performance may be slightly improved by dynamic warm-up. For my money, however, it is tiring and not worth the candle – I would rather just get on with it.

Cooling down

The cool down is another appealing idea – and has more evidence to support it than warming up.. At the end of a session you are likely to be hot, sweaty with your blood vessels dilated. If you just stand about at this stage your heart rate falls but your blood vessels tend to remain dilated to promote heat loss. As a result your blood pressure falls – which may cause you to feel faint or even keel over. Not dangerous but preventable by cooling down – keeping moving until your blood vessels have contracted enough to prevent the fall in blood pressure.

Exercise types

There are two broad categories of exercise. Dynamic or isotonic exercise is that which uses the regular, purposeful movement of joints and large muscle groups, particularly their Type I fibres. Isometric exercise, on the other hand, involves static contraction of muscles with little or no joint movement, predominantly involving Type II fibres. Other descriptors of exercise category include aerobic (using oxygen) and anaerobic (not needing oxygen). Most activities involve a combination of these factors and classification is typically expressed as the dominant characteristics of the particular exercise.

Aerobic exercise

Dynamic or aerobic exercise is exemplified by such sports as running, cycling, swimming and aerobic dance. They involve much movement and little strength and can be continued for long periods and are sometimes referred to as “cardiovascular” workouts. They are dependent on a good supply of oxygen which fuels the energy produced by the breakdown of glycogen stored in the muscle. Such exercise, performed at the right level, can be continued as long as there is a sufficient supply of carbohydrate (sugar) in the form of glycogen. If the duration and intensity of the exercise is sufficient to deplete the glycogen stored faster than it can be replenished, muscle fatigue sets in and the exercise must be greatly reduced or stopped. This is the experience of the marathon runner who “hits the wall”. The effort of aerobic exercise is mainly performed by Type I, or slow twitch, muscle fibres. Most of the clinical benefits of exercise in preventing and treating chronic diseases have been demonstrated for aerobic exercise and it is this form of exercise which is the main subject of my blogs.

Isometric exercise

Anaerobic or isometric exercise involves much strength but little movement. More mature readers will remember the once well-known Charles Atlas muscle building techniques. These were pure isometrics, involving one muscle group straining against another without movement – a form of exertion designed to build up muscle bulk. The muscle fibres used are the Type II, or fast twitch fibres. They do not use oxygen and they quickly fatigue. Most so called anaerobic exercises do involve some movement but make much more use of strength. Examples are weight lifting and sprinting. In the clinical context, isometric exercise is much used by physiotherapists in the treatment of joint injuries and after orthopaedic surgery. Muscle strengthening is also very important in the treatment of frailty and balance problems in old age – both of which I have discussed in the past and will certainly return to in the future.

Subscribe to the blog

Categories

- Accelerometer

- Alzheimer's disease

- Blood pressure

- BMI

- Cancer

- Complications

- Coronary disease

- Cycling

- Dementia

- Diabetes

- Events

- Evidence

- Exercise promotion

- Frailty

- Healthspan

- Hearty News

- Hypertension

- Ill effects

- Infections

- Lifespan

- Lipids

- Lung disease

- Mental health

- Mental health

- Muscles

- Obesity

- Osteoporosis

- Oxygen uptake

- Parkinson's Disease

- Physical activity

- Physical fitness

- Pregnancy

- Running

- Sedentary behaviour

- Strength training

- Stroke

- Uncategorized

- Walking

I always do and did a warm down, but on the subject of ‘warming up’ for exercise, as a swimmer I used to do very little warm up, just a couple of minutes. However when I ‘joined’ Cardiac Rehab 5 years ago, I thought the importance of warming up for the heart muscle was emphasised and now I tend to do about 10 minutes warm up, gradually increasing the exercise, for my heart.

Is this not really necessary?

Thanks Pauline

Our exercise instructors do ensure an adequate warm up for all. This is important for those with a very limited exercise tolerance and a good way for anyone to “get going”. My point is that those benefits are limited and that you do not need to spend too much time on warming up if that lessens your time on more vigorous effort. Your 10 minutes warm routine seems very reasonable.