Encouraging exercise Part 2

Last week I discussed the importance of starting young and also the role of the medical profession in promoting exercise. Sadly doctors do not encourage their patients to exercise enough and when they do their advice is seldom heeded!

Other ideas

The British Heart Foundation (BHF) 2015 publication ‘Physical Activity Statistics’ includes a number of ideas for increasing physical activity in adults:

- Workplace interventions Adults spend up to 60 per cent of their waking hours in the workplace, which should therefore be a useful place to start. Such initiatives include creating workplace exercise facilities, providing one-to-one exercise advice, encouraging the use of stairs rather than lifts, providing short breaks during the working day for employees to engage in physical activity. The Alberta Centre for Active Living (ACAL) in Canada has analysed some of the factors currently used to encourage increased physical activity in the workplace. They include challenges and competitions (pedometer challenges, physical activity and sedentary time), information and counselling (posters and handouts, individual and shared counselling), organisational (regular active breaks and moving about), the physical environment (office layout, active workstations, secure bike racks). Again, the effects of these measures are limited. One multi-intervention health programme trial of 160 work sites did achieve an increase in self-reported physical activity at 18 months, but produced no change in any clinical outcomes such as blood pressure, blood cholesterol or BMI.

- Environmental interventions Improving the environment in a number of ways can encourage exercise – walking and biking trails, outdoor gyms, traffic calming, encouraging ‘active travel’ – i.e. walking or cycling rather than taking the bus or train and notices promoting the use of stairs rather than lifts in public places. Residents living in neighbourhoods where it is easy and pleasant to walk have less likelihood of developing some health problems, such as pre-diabetes. Evidence from existing low-traffic neighbourhoods is encouraging. The London Borough of Waltham Forest has implemented growing numbers of these neighbourhoods since 2015. A survey found that after three years residents had increased their walking by 115 minutes and cycling by 20 minutes per week relative to people living elsewhere in Outer London.

In the United States, Active Living Research has expanded the theme by specifying some of the environmental improvements that can encourage greater physical activity, including aesthetics of the area, plenty of vegetation, parks with open vistas, perceived safety from traffic and crime, general neatness, and play and exercise equipment. The importance of a good exercise environment was shown by the International Physical Activity and Environment Network. Across 14 cities on five continents, the difference in physical activity between participants living in the most and the least activity-friendly neighbourhoods ranged from 68 minutes per week to 89 minutes per week.

- Active commuting, defined as walking or cycling to work, has been shown to be positively associated with physical fitness and also with lower BMI, obesity, blood pressure and insulin levels. Active commuting reduces heart disease, cancer and age-related mortality, cycling being more effective than walking. The bicycle-hire system in major cities (e.g. ‘Boris Bikes’ in London) has increased active travel. Sustrans (sustrans.com) is a charity which aims to enable and increase public exercise by walking, cycling and using public transport (which involves walking to and from bus stops, stations, etc.), leading to healthier, cheaper journeys. Their flagship project is the National Cycle Network, which has created over 14,000 miles of signed cycle routes throughout the UK, although about 70 per cent of the network is on previously existing, mostly minor roads where motor traffic will be encountered. On the downside, it is to be deplored that some train companies prevent the carriage of bicycles on commuter trains.

- Community interventions Social-support systems, group activities, buddy systems and ‘Walking for Health’ groups all promote more exercising, though to a limited degree. Telephone support and mass-media campaigns have their place.

- Jogging and running Another initiative has been the parkrun scheme – every Saturday morning some 300 parks around the country host 5km runs without charge. About 50,000 runners are out there each weekend. An excellent introduction to this form of exercise is the ‘Couch to 5k’ initiative, which helps anyone to get off the sofa and gradually increase their activity level to walking/walk-jogging/jogging 5k. The programme is supported by a website, a phone app and plenty of available encouraging and motivating podcasts.

- Internet-delivered interventions A number of schemes to increase physical activity within various populations have been delivered via the internet. This has the benefit of reaching a large number of individuals at a low cost relative to other types of intervention, such as making physical environmental changes or having regular direct contacts with individuals. Internet-delivered interventions have produced positive results, but there is still insufficient evidence of their ability to produce long-term change. They have the particular advantages of providing easy self-monitoring and feedback information and enabling communication with health professionals or other users via email and chat. Many people find that feeding their accelerometer results on to a website allows them to follow their performance. Comparing it to that of others should be an effective incentive.

- Smartphone apps for encouraging exercise. Some concentrate on helping with behavioural change. Others measure activity, like the pedometer apps and the Public Health England app ‘Active 10’. Results of exercise sessions, for instance runs, can be uploaded to a website which will track your performance and compare it with previous performances or compare you with other participants. The idea is that competition is a stimulus and should encourage you to keep exercising or even up your game. So far, there is little evidence of their efficacy in increasing exercise in either the short or the long term. One block to their implementation is the need for the user to be motivated to take exercise in the first instance. One hopeful development has been an app that is a game that demands physical activity. A randomised controlled trial of use of the game for 24 weeks in 36 type 2 diabetics found an increase in walking of 3,128 daily steps and increase in peak oxygen uptake of 1.9ml/min/kg – but, sadly, inadequate exercise and inadequate compliance led to no change in diabetic control.

- Pedometers At an individual level, sedentary individuals can do much for themselves by just getting out of the chair and walking about for a few minutes every hour, going out for short walks, pacing about when answering the telephone. A pedometer or fitness tracker is an excellent addition to the armamentarium for encouraging increased exercise. Worn regularly, it provides the baseline and allows you to set targets that are easily monitored.

Such ‘trackers’ ‘come in a variety of forms with a variety of characteristics. They can monitor movement, calories burned, heart rate and even sleep patterns. The Consumers’ Association produces a listing of available devices ranging in price from £18 to £700. If you decide that this is the right approach for you, choose one that is appropriate for the sport or activity you wish to track. Sadly, and grist to the mill of pedometer opponents, one controlled trial of weight-loss strategies found that overweight people using exercise trackers lost less weight over two years than their controls who did not use trackers!

- Applying the concept of biological age . It has been suggested that telling patients their biological age, particularly if it is much greater than their chronological age, could be a tool for encouraging them to become more active and thus bring the two ages into harmony.

- Food labelling to include the ‘activity equivalent’ of the calories about to be consumed. The results do not make very comfortable reading, which may be all to the good, provided it does not induce a sense of despair in the consumer. For instance, it takes a person of average weight about 26 minutes to walk off the calories in a can of fizzy drink. It takes a run of about 43 minutes to burn off a quarter of a large pizza – oh dear . . .

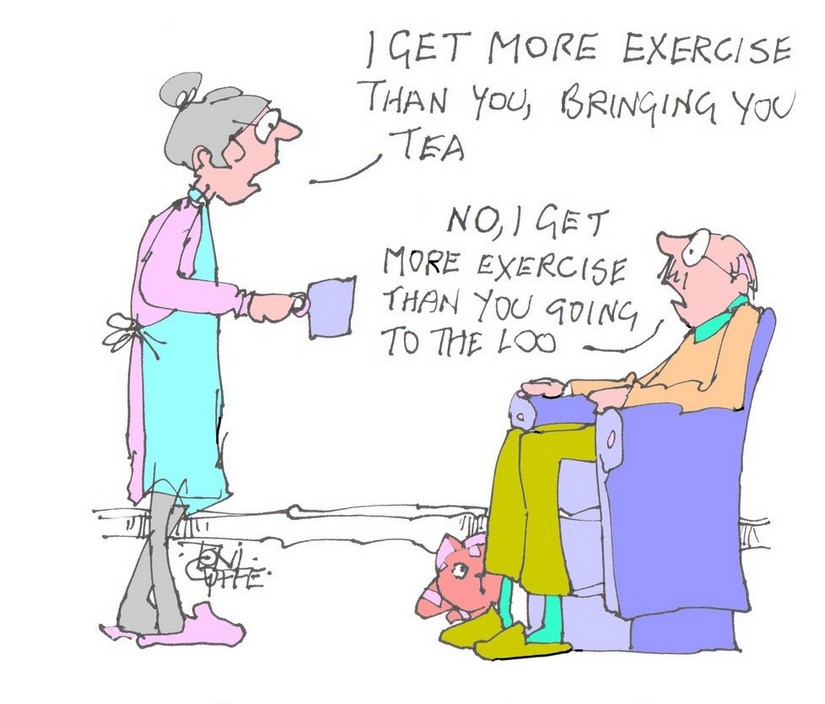

- Reducing exercise targets, particularly for older people. The thinking is that for some folk even the rather modest goals set by the DoH and other national bodies may be a turn-off. Setting lower targets may help older sedentary people to move towards recommended activity levels – all exercise is good and a little is a lot better than none. As a review by the National Institute for Health Research said: ‘older people are more likely to keep active through structured group activities than exercising on their own at home. The social aspect of exercise and activity are particularly important. Successful approaches include walking programmes tailored to older people.’

- Walking An analysis of the trials of physical-activity promotion in 1996 concluded that ‘interventions that encourage walking and do not require attendance at a facility are most likely to lead to sustainable increases in overall physical activity. Brisk walking has the greatest potential for increasing overall activity levels of a sedentary population and meeting current public health recommendations.’

Subscribe to the blog

Categories

- Accelerometer

- Alzheimer's disease

- Blood pressure

- BMI

- Cancer

- Complications

- Coronary disease

- Cycling

- Dementia

- Diabetes

- Events

- Evidence

- Exercise promotion

- Frailty

- Healthspan

- Hearty News

- Hypertension

- Ill effects

- Infections

- Lifespan

- Lipids

- Lung disease

- Mental health

- Mental health

- Muscles

- Obesity

- Osteoporosis

- Oxygen uptake

- Parkinson's Disease

- Physical activity

- Physical fitness

- Pregnancy

- Running

- Sedentary behaviour

- Strength training

- Stroke

- Uncategorized

- Walking

Surprised you mention neither e-bikes nor dogs.

Thanks William – good ideas. Whatever motivates you. Dogs are certainly excellent walking machines.