FRAILTY Part 2

The consequences of frailty

The social and financial consequences of frailty are enormous and growing. When frail people become ill they have a higher risk of dying, becoming ill or disabled, or having to be taken into care, than the non-frail and if discharged from hospital have a high rate of readmission – 40 per cent of frail people are readmitted within six months. If they need surgery, frail people are much more likely to suffer complications or die.

Our hospitals are full of ‘bed blockers’ who needed admission only because they were frail and who are unable to go home because of lack of carers and lack of money to pay for them. The frail elderly occupy increasing numbers of beds in residential homes and nursing homes for dependent people. If able to stay at home, they require regular visits from informal or formal carers to allow them to keep a semblance of normal life.

Frail elderly people are major users of emergency medical services, presenting with such problems as falls, immobility, incontinence and confusion. They are at particular risk of falling: 50 per cent of people aged over 80 fall at least once a year and about 5 per cent of these falls result in a fracture, most seriously of the neck of the femur (the hip). Falls are a major threat to older adults’ quality of life, often causing a decline in their ability to care for themselves and to participate in physical and social activities. Fear of falling can lead to a further limiting of activity, independent of injury. Current estimates are that falls cost the NHS more than £2.3 billion per year.

We have a growing army of dependent elderly people, with increasing social-care costs, increasing difficulty in finding enough younger carers and an inability to afford them. The trajectory of this problem is inexorably upwards, with the proportion of the population aged over 80 set to double over the next 40 years, while the number of over-85s requiring 24-hour care is also expected to double to 446,000, a staggering number. The media frequently publicise the crisis in social-care funding. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has predicted that, unless they are bailed out by the government, local councils will have to spend up to 60 per cent of their revenues on social care by 2034. The problems of caring for our ageing population will be compounded by cuts in funding and by the restriction of immigration on which staffing depends.

The role of unfitness in frailty

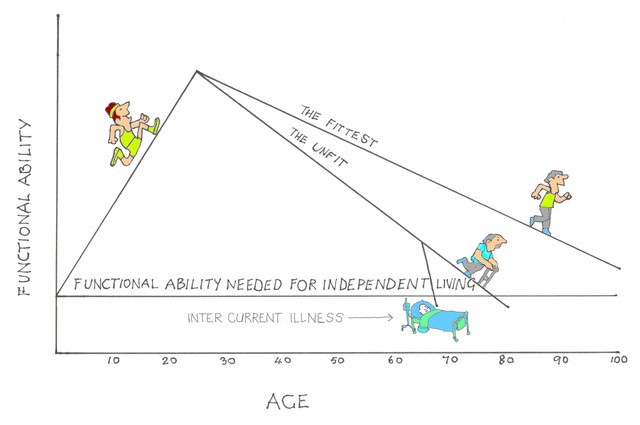

Frailty goes hand in hand with end-of-life dependence. The doctor and public health consultant Sir John Muir Grey has used a series of graphs to illustrate the effect of physical fitness on ability to live independently. The illustration at the head of this blog is derived from these graphs and shows the result of the decline in function on ability to live independently.

We all deteriorate in ability as we age but the fitter we keep ourselves, the slower that rate of decline and the flatter the trajectory of reducing function. We can remain independent only if our ability is maintained above a certain level, shown on the illustration as the horizontal line. The less able we are, the earlier in life will we hit that line.

Things can get worse, because the frail elderly are particularly vulnerable to acute deterioration in health, mainly due to falls, fractures and infections. Such events lead to a sudden steepening of the curve of loss of function so that the line of dependency is reached much earlier.

And worse still is to come – hospitalisation. In hospital, immobility is the rule, a result both of the reason for admission and of the usual hospital culture of bed-rest for poorly patients. Unfortunately the frail elderly not only start with reduced muscle mass and strength but also, when bed-rested, suffer a more rapid further loss than younger subjects. For many this is the last straw in their goal of maintaining independence. They become stuck in hospital awaiting long-term care where that can be found. This disastrous progression of disability can be partly ameliorated by planned inpatient exercise programmes and these are now being implemented in many geriatric departments, with some success.

Healthspan

Next week I will talk about healthspan – the duration of healthy life I believe that this is much more important than lifespan – the total duration of life.

Subscribe to the blog

Categories

- Accelerometer

- Alzheimer's disease

- Blood pressure

- BMI

- Cancer

- Complications

- Coronary disease

- Cycling

- Dementia

- Diabetes

- Events

- Evidence

- Exercise promotion

- Frailty

- Healthspan

- Hearty News

- Hypertension

- Ill effects

- Infections

- Lifespan

- Lipids

- Lung disease

- Mental health

- Mental health

- Muscles

- Obesity

- Osteoporosis

- Oxygen uptake

- Parkinson's Disease

- Physical activity

- Physical fitness

- Pregnancy

- Running

- Sedentary behaviour

- Strength training

- Stroke

- Uncategorized

- Walking

Well done Hugh. A really intersting first two of the series – scary!!

David

Many thanks David. Someone as fit as you does not need to be scared!