Recent advances – Frailty Part 2

Apologies

Many more apologies for the false start last weekend – here is the Blog which nearly got sent by mistake!

Frailty

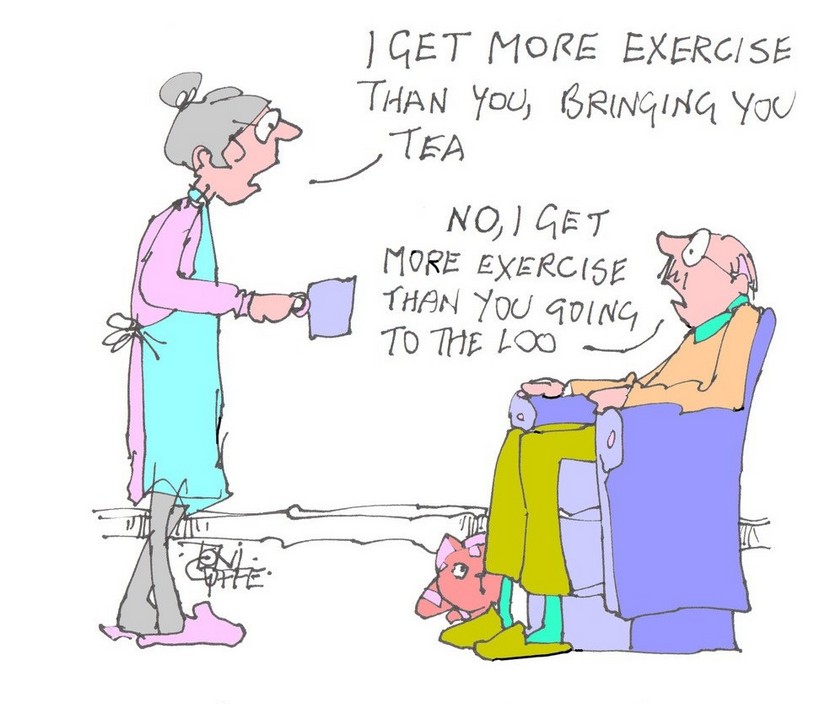

Last time I gave you the long definition of Frailty. Here’s the short version – “old and feeble”. Some of the essential features include low grip-strength, low energy, slowed walking speed, low physical activity, and/or unintentional weight loss.

What about the causes and the prevention/treatment of frailty? Well the “old” bit is hard to combat, but the feeble bit can be both prevented and treated.

Causes of frailty

Frailty is a condition of general weakness and debility. It is often seen as an inevitable consequence of the ageing process. As we age we all lose muscle mass and strength, a condition called sarcopenia. A degree of age-related sarcopenia is unavoidable, but the rate at which we lose muscle is largely dependent on how much exercise we take.

By the seventh and eighth decade of life skeletal muscle strength is decreased on average by 20–40 per cent for both men and women. Most of this loss of strength is caused by decreased muscle mass. The resulting progressive loss of muscle power leads to increasing disability and loss of independence. The prevalence of sarcopenia increases with each five-year age group, from about 15 per cent among 65–70-year-olds to as much as 50 per cent in over-85s and probably becoming increasingly common thereafter. It accelerates with the passing of the years.

Frailty is associated with poverty and low social status. The British Medical Journal has recently highlighted the increasing prevalence of frailty in our senior citizens and concluded that government policy has contributed – by austerity policies with cuts in public sector spending on welfare and social care.

Prevention of frailty

Regular exercisers are at low risk of developing frailty later in life. To gain the most from physical activity, it should start early in life and be continued throughout life. Patterns of behaviour are established in childhood and adolescence. Making substantial changes later in life becomes increasingly difficult. It seems to me that making exercise part of our culture is crucial in the prevention of frailty.

“Physical inactivity and social isolation accompanying ageing leads to decline in muscle strength, muscle mass and accelerates frailty, worsens chronic health issues, including hypertension, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, depression and dementia. Presently, there are no pharmacological agents (or combinations) or care standards known to slow down ageing. Physical activity including exercise training have been shown to influence key drivers of ageing …. Exercise improves physical function and quality of life, reduces the burden of non-communicable diseases and premature overall mortality including cause specific mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and chronic lower respiratory tract diseases …… Population level preventive efforts ideally before the onset of functional decline have been tried out and tested in many countries. Unfortunately, a limited amount of physical exercise strategies are planned to minimize exercise-related impact on function and/or ability to perform ADLs .” (1)

An epidemiological approach to the causes of frailty is to look at the characteristics of communities of those who age particularly well – so called “super-agers”. A study of 64 people aged 80+ who had superior cognitive function was compared with a group of ‘normal’ individuals of the same age. The super-agers had superior mobility and fine motor skills and had been more active in their middle years -both their minds and their bodies had benefited. (2)

There is plenty of evidence that high levels of physical activity throughout life are associated with reduced risk of developing frailty – but also with higher levels of quality of life. A study of 1,433 subjects aged 60 or more measured quality of life (QoL) at baseline and then 6 years later. It found that over that period, both more time being active and less time sitting down were associated with higher QoL scores (3).

Treatment of frailty

Exercise is key to the management of frailty and, since sarcopenia is the main driver of frailty, muscle strengthening is key. A recent systematic analysis looked at the effectiveness of different approaches to frailty in 69 randomised trials with more that 27,000 participants aged 60+ . The most effective was physical activity (PA) and, of the various forms of PA, resistance training was the best.(4)

Doctors need to encourage their older patients to be as active as possible. They should make as much use as possible of community exercise facilities. These include prescription of exercise by referral to the local Sports Centre or encouragement to use such approaches as the “couch to 5k” initiative. In Alton we have investigated local provision and produced a website detailing all the exercise clubs and other such facilities in our area. For the older folk who are unlikely to use the internet as their source of such information we have produced and spread as widely as possible a booklet with the same details.

In hospital

An important opportunity to reduce the rate of progression of frailty is in the management of acute illness/injuries. Admission to hospital can be a disaster for the frail/pre-frail individual. Every day as an in-patient can result in a 5% loss of muscle strength. The first priority must be to avoid admission if at all possible. Failing this, a culture of PA in the hospital could help the patient to retain or even improve mobility – but this would require a huge increase in spending on physiotherapists as well as a change in the mindset of the nursing staff.

The bottom line

The most recent research suggests suggests that the best treatment of sarcopenia and the resulting frailty is increasing exercise levels with a combination of muscle strengthening and aerobic exercise. Ensuring adequate protein intake is also important.

1. Merchant, R.A. et al, J Nutr Health Aging 25, 405–409 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-021-1590-x

2. Calandri IL et al. Dement Neuropsychol. 2020 Dec;14(4):345-349. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642020dn14-040003. PMID: 33354286; PMCID: PMC7735051.

3. Yerrakalva et al. (2023) DOI:10.1186/s12955-023-02137-7

4. Sun X et al. doi:10.1093/ageing/afad004

Subscribe to the blog

Categories

- Accelerometer

- Alzheimer's disease

- Blood pressure

- BMI

- Cancer

- Complications

- Coronary disease

- Cycling

- Dementia

- Diabetes

- Events

- Evidence

- Exercise promotion

- Frailty

- Healthspan

- Hearty News

- Hypertension

- Ill effects

- Infections

- Lifespan

- Lipids

- Lung disease

- Mental health

- Mental health

- Muscles

- Obesity

- Osteoporosis

- Oxygen uptake

- Parkinson's Disease

- Physical activity

- Physical fitness

- Running

- Sedentary behaviour

- Strength training

- Stroke

- Uncategorized

- Walking

Good blog you have got here.. It’s hard to find good quality writing like yours

nowadays. I honestly appreciate people like you! Take care!!

Merci beaucoup Indira

Hugh